Significant Dates for Indigenous Australians in March

In March, we commemorate the anniversaries of significant events for Australia's First Nations people:

~ 21 - 22 March 1797: The Battle of Parramatta

~ 21 March 1837: Death of Luggenemenener

~ 21 March 2024: National Close the Gap Day

~ 23 March 1998: The Mirrar Aboriginal people from Kakadu begin a blockade of the Jabiluka uranium mine

~ 23 March 2022: World No. 1, Ash Barty announced her retirement from tennis

~ 27 March 1905: Birth of Jack Patten, Aboriginal Civil Rights Leader

~ 29 March 1881: William Barak delivered a petition from the Coranderrk Aboriginal reserve to Parliament House in Melbourne

21 - 22 March 1797: The Battle of Parramatta

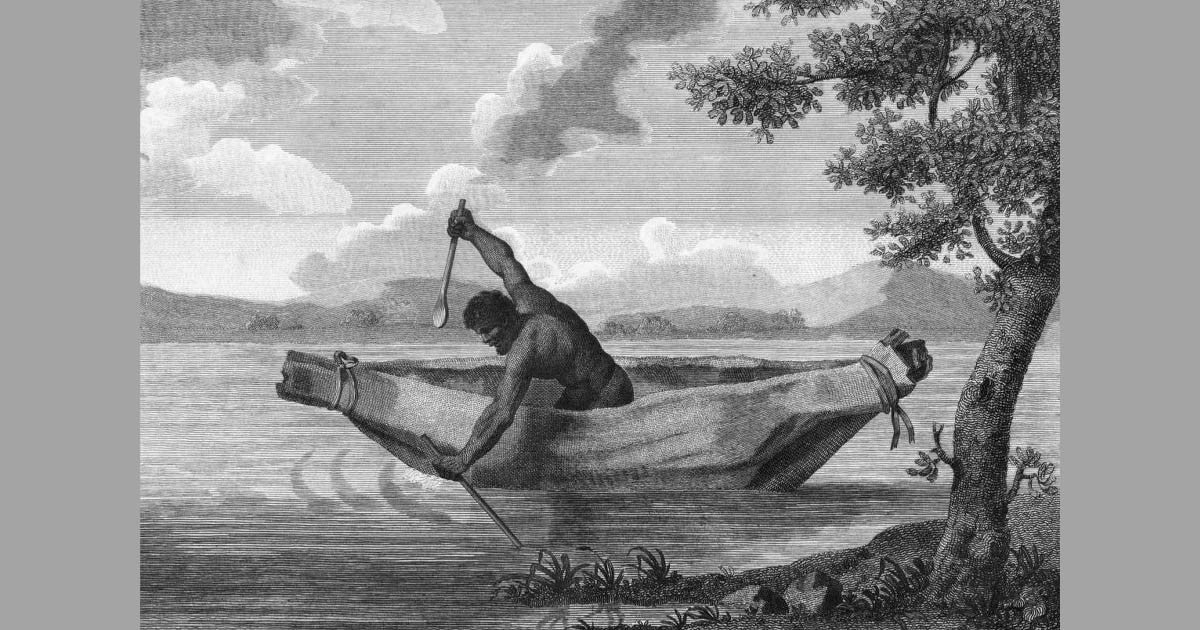

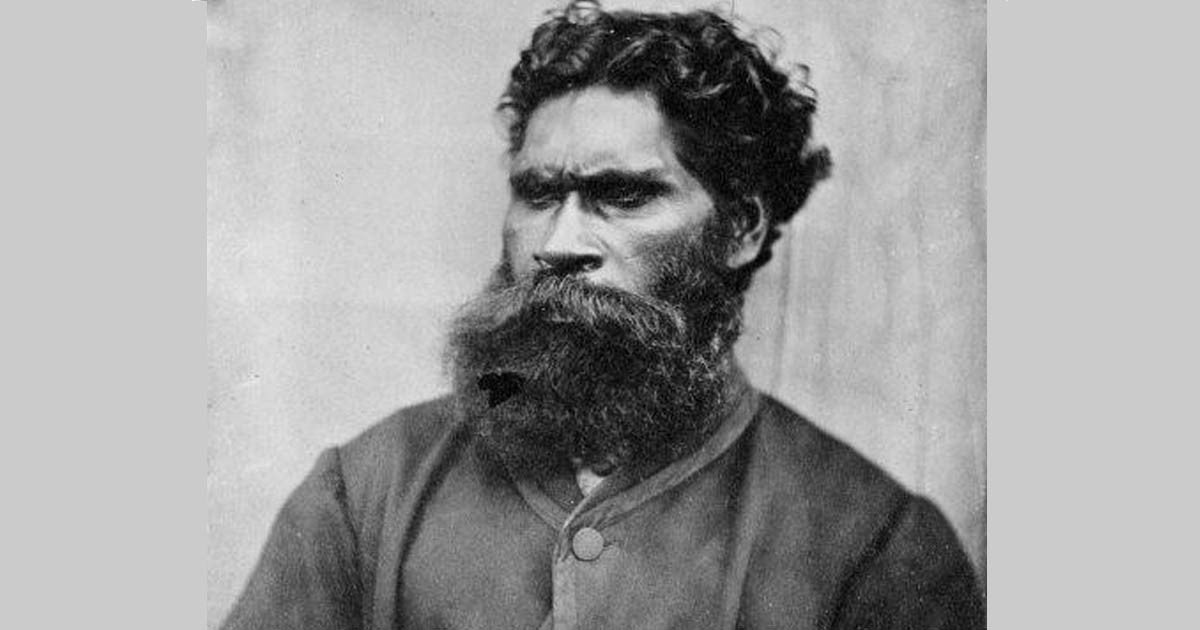

Pemulwuy, the leader of the Bidjigal Aboriginal resistance to British colonisation. By Samuel John Neele (1758-1824) - State Library of Victoria

Pemulwuy, the leader of the Bidjigal Aboriginal resistance to British colonisation. By Samuel John Neele (1758-1824) - State Library of Victoria

The Battle of Parramatta stands as a significant event in the Australian Frontier Wars. In the mid-1790s, the Northern Farms region around Parramatta was opened up to British colonists through land grants, marking the beginning of conflict with the original landowners, the Bidjigal Aboriginal people.

Led by Pemulwuy, groups of Bidjigal warriors launched raids on the Northern Farms in early 1797. In response, colonists armed themselves and sought reinforcements from British soldiers stationed at Parramatta. On 21 March 1797, they formed a party to hunt down local Aborigines.

On 22 March 1797, when Pemulwuy's warriors approached Parramatta, a violent confrontation ensued. Despite their courage, the Bidjigal warriors who were armed only with spears faced overwhelming firepower. Five warriors were killed instantly when soldiers opened fire.

Pemulwuy was shot seven times and critically wounded. He was captured by soldiers but managed to survive his wounds and escape some weeks later, still in his leg irons. His seemingly miraculous survival earned him a reputation for invincibility against British firearms among his people.

The Bidjigal resistance to the British invaders persisted, prompting the colonial government to issue an order for Pemulwuy's capture, dead or alive, with a reward offered. In June 1802, Pemulwuy was fatally shot. Following his death, his head was cut off and sent to England, eventually sparking demands for its repatriation by Sydney's Aboriginal communities.

Efforts to locate Pemulwuy's skull have led to various trails, including inquiries with the Natural History Museum in London. Despite these efforts, the skull remains elusive among the estimated 3,000 Aboriginal remains held in the UK.

21 March 1837: Death of Luggenemenener

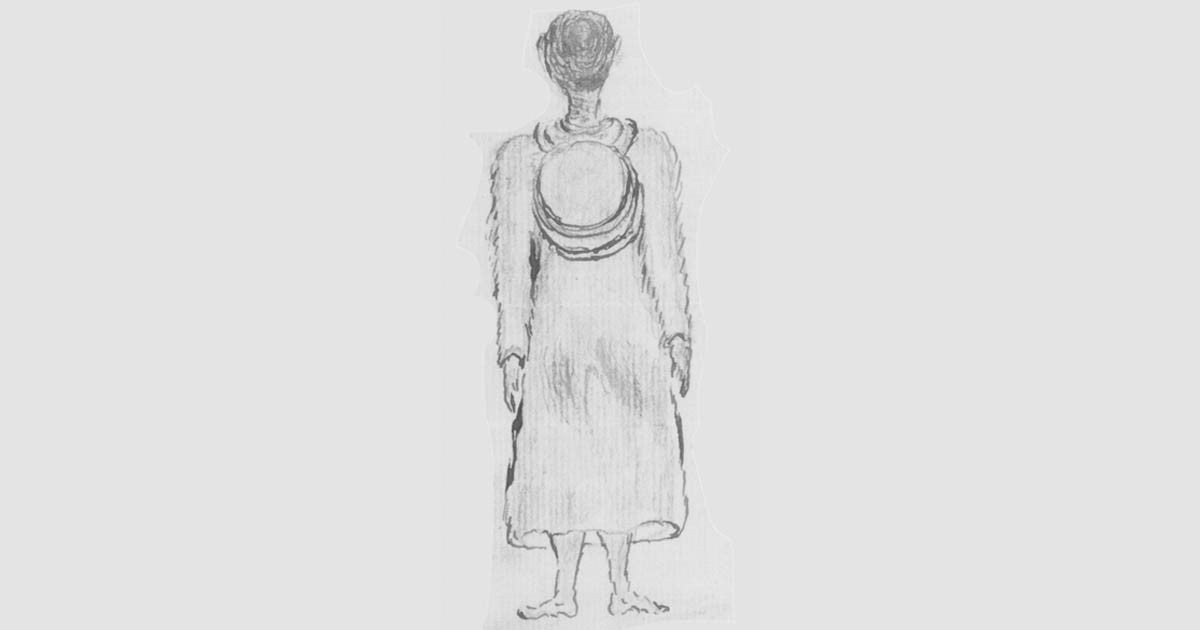

Luggenemenener, a drawing in pen and black ink and black pencil and wash by George Augustus Robinson, 1832, Hobart, Tasmania, in George Augustus Robinson Journal, National Gallery of Australia, 2018, The National Picture: The art of Tasmania’s Black War, Canberra.

Luggenemenener, a drawing in pen and black ink and black pencil and wash by George Augustus Robinson, 1832, Hobart, Tasmania, in George Augustus Robinson Journal, National Gallery of Australia, 2018, The National Picture: The art of Tasmania’s Black War, Canberra.

The illustration shows the traditional mourning disc, which Luggenemenener wore on her back every day, demonstrating the intense physicality of her ritual grief. The weight of the disc burdened her as a constant reminder of lost loved ones and her young son. Luggenemenener is remembered as a young woman living far from her Turapina homelands, marooned on a Bass Strait Island, her child taken from her, and her people murdered.

Luggenemenener (c. 1800 – 21 March, 1837) was a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman of the early nineteenth century. She was born on the traditional homelands of her Plangermaireener ancestors in the Turapina region of north-east Tasmania, later named Ben Lomond by the British colonists. The Turapina region was home to at least three Aboriginal clans, the Plangermaireener, Plindermairhemener and Tonenerweenerlarmenne.

Luggenemenener was a mother to three sons: Walter, Maulboyheener, and Rolepana. Walter's father was Rolepa, a leader of the Plangermaireener clan. During 1828-1830, John Batman, a former convict who was later to become known as Melbourne's "founding father," led the infamous 'roving parties' in Tasmania to suppress the Aboriginal inhabitants and seize their land near Turapina.

Luggenemenener's act of maternal bravery occurred in 1829 when she shielded her young son, Rolepana, from the roving party's onslaught, saving his life. Unfortunately, Luggenemenener and Rolepana were captured soon afterward by Batman. He sent Luggenemenener to Campbell Town jail and Rolepana to his farm, "Kingston," where he was made to work as a labourer.

Batman's land grant, initially 500 acres, expanded to 7,000 acres over time. The land grants were given to colonists as reward for the atrocities they committed against the Aboriginal population to drive them from their ancestral homelands.

Colonial authorities hastened the dispossession of the Tasmanian Aboriginal population with the “Black Line”. This barrier was established to shield against Aboriginal attacks as colonisation expanded into their territory. Defended by about 2,200 men, including soldiers, civilians, and 1,200 convicts, it aimed to fortify colonial positions against Aboriginal resistance.

In 1830, Batman granted Luggenemenener conditional freedom, tasking her with persuading her tribe to surrender to authorities. However, she had no intention of betraying her people or returning to captivity.

Despite Luggenemenener's efforts remain free, the Black Line soldiers eventually captured her, leading to further imprisonment.

In 1830, she, along with the remaining Tasmanian Aboriginal population, was exiled to Flinders Island's Settlement Point. These 160 survivors were deemed by colonial authorities to be safe from further violence, but the exile camp was plagued by harsh conditions and disease. Luggenemenener passed away on March 21, 1837, remembered for her resilience in the face of displacement and tragedy.

Rolepana never reunited with his mother or her people and died in Melbourne in 1842.

Luggenemenener's legacy endures as a symbol of strength and resistance against the injustices inflicted upon Tasmania's Aboriginal population during a dark period of brutal colonisation and genocide.

21 March 2024: National Close the Gap Day

National Close the Gap Day serves as an important platform for Australians to unite in addressing the enduring 17-year life expectancy gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

The Close the Gap campaign originated in April 2007, spurred by Professor Tom Calma's 2005 Social Justice report, which underscored health as a fundamental human right. Subsequently, the Australian government embraced the Close the Gap goals in 2008 and launched the Closing the Gap strategy. A commitment to delivering an annual progress report to Parliament on the strategy's advancement was made in 2009.

In 2020, the Closing the Gap framework underwent substantial revision, with a renewed emphasis on fostering partnerships between governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This shift signalled a recognition of the importance of collaboration in achieving meaningful progress.

Annually, the Close the Gap Steering Committee releases a comprehensive report detailing the Government's efforts and achievements in pursuing its targets. These reports serve as critical accountability measures and provide insights into areas needing further attention and improvement.

On 13 February 2024, the Prime Minister presented the Commonwealth Closing the Gap 2023 Annual Report and 2024 Implementation Plan, outlining the ongoing commitment and action towards bridging the health disparity gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. This event accentuates the significance of sustained efforts and collaborative approaches in addressing the systemic health challenges faced by Indigenous people and their communities across Australia.

Links to the Commonwealth Closing the Gap 2023 Annual Report and 2024 Implementation Plan are at:

https://www.niaa.gov.au/resource-centre/indigenous-affairs/commonwealth-closing-gap-2023-annual-report-and-2024-implementation-plan

23 March 1998: The Mirrar Aboriginal people from Kakadu begin a blockade of the Jabiluka uranium mine

An aerial view of the Jabiluka Uranium Mine development site. The large pond is the "Jabiluka Total Retention Pond" and the entry to the shaft is visible at the far edge of the cleared area.

An aerial view of the Jabiluka Uranium Mine development site. The large pond is the "Jabiluka Total Retention Pond" and the entry to the shaft is visible at the far edge of the cleared area.

Following decades of opposition to uranium mining, on 23 March 1998, the Mirrar people called on supporters from around Australia to take part in blockading the construction of the Jabiluka uranium mine on their ancestral homelands.

Over a period of eight months, thousands took part and around 600 people were arrested for disrupting work whilst protests and actions took place around the rest of country, including bank boycotts, high-school walkouts, and the shutting down of mine operator, North Ltd’s Melbourne headquarters for several days.

Continued resistance by the Mirrar prevented the mine from opening and the project was cancelled five years later.

The Jabiluka Long-Term Care and Maintenance Agreement signed in February 2005 gives the traditional owners veto rights over future development of Jabiluka. However, in 2007, Rio Tinto suggested that the mine could reopen one day.

Note on uranium mining in Kakadu: Technically the site of the Ranger uranium mine and the adjacent Jabiluka area are not part of Kakadu National Park, but are completely surrounded by it, as they were specifically excluded when the park was established from 1981. Uranium mining in the area remains a subject of controversy. There have been more than 150 leaks, spills and licence breaches at the Ranger uranium mine since it opened in 1981. As of March 2009, the Ranger uranium mine is leaking 100,000 litres per day of contaminated water into the ground beneath the Kakadu National Park, according to a government appointed scientist. Energy Resources of Australia has been repeatedly warned about its management of the mine.

23 March 2022: World No. 1, Ash Barty announced her retirement from tennis

Sydney, Australia - 6 January 2019: Australia's Ash Barty on-board the super yacht 'Cooroboree' during a media opportunity for the Sydney International tennis. Photo by Rob Keating from Canberra, Australia/robiciatennis.com

Sydney, Australia - 6 January 2019: Australia's Ash Barty on-board the super yacht 'Cooroboree' during a media opportunity for the Sydney International tennis. Photo by Rob Keating from Canberra, Australia/robiciatennis.com

Ashleigh Jacinta Barty AO was born on 24 April 1996, in Ipswich, Queensland. She is of Ngaragu descent, tracing her Indigenous Australian heritage through her great-grandmother to the Aboriginal people of southern New South Wales.

Barty's tennis career is marked by outstanding achievements. Following in the footsteps of Evonne Goolagong, she became the second Indigenous Australian tennis player to attain the world No. 1 ranking in singles by the Women's Tennis Association (WTA), holding the prestigious title for a total of 121 weeks.

Barty boasts three Grand Slam singles titles, triumphing at the 2019 French Open, the 2021 Wimbledon Championships, and the 2022 Australian Open.

Barty’s journey in tennis commenced at the age of four in Brisbane, Queensland. She showed early promise in her junior career, attaining a career-high ranking of No. 2 in the world after clinching the 2011 Wimbledon girls' singles title at just 14 years old.

During a hiatus from tennis in 2014, Barty ventured into cricket, signing with the Brisbane Heat for the inaugural Women's Big Bash League season.

Returning to tennis in 2016, Barty's career gained momentum. She secured her first WTA title at the Malaysian Open in 2017 and ascended to No. 17 in the world rankings. Subsequent years saw Barty excel in both singles and doubles, with notable achievements including her victory at the 2019 French Open and a runner-up finish at the 2019 Fed Cup.

Despite her slight stature, Barty is renowned for her prowess on the court, dominating with her skillful play, showcasing her versatility and exceptional serve.

Barty served as the National Indigenous Tennis Ambassador for Tennis Australia, actively promoting Indigenous participation in the sport.

In a surprise announcement on 23 March 2022, Barty declared her retirement from tennis, relinquishing her No. 1 singles ranking. Citing a lack of physical and emotional drive, she concluded her illustrious career at its pinnacle. Barty became only the second tennis player ever to retire while holding the No. 1 ranking, after Justine Henin in 2008.

Barty's contributions extend beyond tennis; she embraces her Indigenous heritage and serves as an ambassador advocating for increased Indigenous involvement in tennis. Honoured with accolades such as the Young Australian of the Year in 2020, she remains a celebrated figure in both the sports world and Indigenous communities.

Barty married Australian professional golfer Garry Kissick on 23 July 2022. The couple welcomed their first child on 3 July 2023, marking a new chapter in Barty's remarkable journey.

27 March 1905: Birth of Jack Patten, Aboriginal Civil Rights Leader

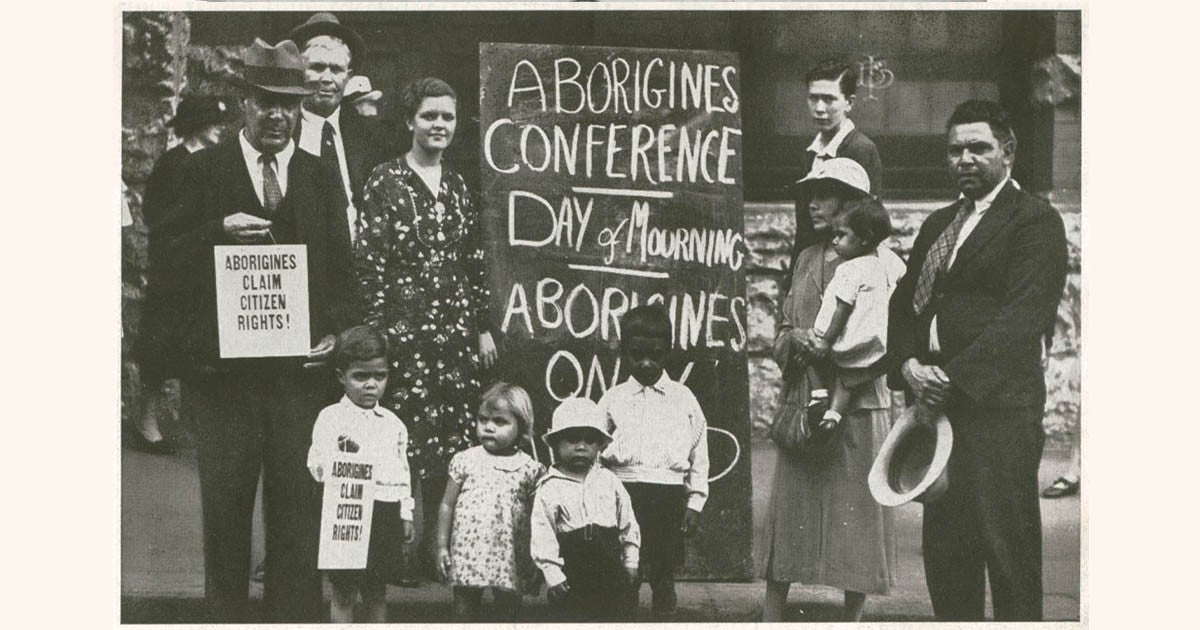

First Nations Indigenous Australian protest, "Day of Mourning", 1938, Russell Clark, from photo-mechanical print published in 'Man' magazine, State Library of New South Wales

First Nations Indigenous Australian protest, "Day of Mourning", 1938, Russell Clark, from photo-mechanical print published in 'Man' magazine, State Library of New South Wales

John Thomas “Jack” Patten (27 March 1905 – 12 October 1957) was an Aboriginal Australian civil rights activist and journalist born at the Cummeragunja Aboriginal reserve in southern New South Wales.

Patten co-founded the Aborigines Progressive Association in 1937 and organised the 1938 Day of Mourning protest. He led efforts for Aboriginal citizenship rights, presenting a 10-point plan to Prime Minister Joseph Lyons. In 1938, Patten also established The Abo Call, an Aboriginal newspaper.

Patten played a key role in the Cummeragunja walk-off in 1939, advocating against government mistreatment of Aboriginal workers and their families. The walk-off was a pivotal protest by Aboriginal residents at the Cummeragunja reserve.

Originally inhabited mostly by Yorta Yorta First Nations people, Cummeragunja had faced neglect from Christian churches and increased government control. By late 1938, dissatisfaction had grown due to poor living conditions and restrictions.

On 4 February 1939, Patten visited Cummeragunja at the request of his father who was a resident on the reserve. Patten addressed a large gathering of Aboriginal people in relation to the deteriorating conditions and the intimidation to which the residents were being subjected to under the government appointed manager. Patten raised the subject of New South Wales government plans for the removal of Aboriginal children and gave clarity to the reserve’s residents regarding their rights.

Patten convinced residents to leave the reserve, in an event which would come to be known as the Cummeragunja walk-off. For his part in the protest, Patten was arrested for "inciting Aborigines".

Over 200 residents of Cummeragunja left the reserve and crossed the Murray River, leaving the state of New South Wales. This was in contravention of rules set by the New South Wales Board for the Protection of Aborigines.

Many of the people who left the mission in February 1939 settled in northern Victoria in towns such as Barmah, Echuca and Shepparton. The walk-off was one of the first mass protests by Indigenous Australians in the twentieth century, and had a significant impact on events that followed later, such the 1967 referendum.

Throughout 1939, Patten led a campaign for Aboriginal people to be able to serve in the Australian armed forces. Previously, Aboriginal people had served in every major Australian conflict, but were required to provide proof that they were of substantial non-Aboriginal ancestry. Following a successful campaign, Patten enlisted in the Australian Army, serving with the 2nd AIF in the Middle East. He was discharged in 1942, returning home with a knee badly damaged by shrapnel.

Patten died on 12 October 1957 at the age of 52 after being involved in a motor vehicle accident in Fitzroy in Melbourne.

29 March 1881: William Barak delivered a petition from the Coranderrk Aboriginal reserve to Parliament House in Melbourne

William Barak 1866 photographic portrait by Carl Walter, State Library of Victoria

William Barak 1866 photographic portrait by Carl Walter, State Library of Victoria

Forced from their ancestral lands by British colonists, survivors from the Kulin Nation converged at the Coranderrk Aboriginal reserve in 1863. Coranderrk was located 60 km north east from Melbourne near present-day Healesville. The reserve's creation followed the land occupation and a well organised campaign led by Aboriginal leaders like William Barak and Simon Wonga.

Over the ensuing decades, Aboriginal people from many different tribal groups sought refuge at Coranderrk. The community served as a sanctuary for Aboriginal people amidst the onslaught of frontier violence and European diseases. However, the reserve was subjected to stringent controls by government officials, and its inhabitants fiercely resisted attempts to curtail their autonomy. Their defiance marked one of the earliest campaigns for Indigenous land rights and self-determination.

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, neighbouring pastoralists intensified pressure to dispossess Coranderrk’s residents and divide the 960-hectare land for personal gain. In response, the Coranderrk community launched a protracted struggle to preserve their home. Through petitions, letters to ministers, and direct protest action, they fiercely defended their rights.

On 29 March 1881, faced with imminent threats of closure, William Barak led a 60 km journey from Coranderrk to Parliament House with a deputation of 22 men, to deliver a petition appealing for protection and the reinstatement of a sympathetic manager, John Green. Allies like influential philanthropist, Anne Fraser Bon, bolstered their cause, amplifying their voices. The protests were eventually effective in instigating a Royal Commission and a Parliamentary inquiry into the treatment of Aborigines in the colony of Victoria.

However, in 1886, the Victorian Government enacted the Aboriginal Protection Law Amendment Act, commonly referred to as the 'Half-Caste Act'. This legislation mandated that Aboriginal individuals with European ancestry, aged between 15 and 35, were obligated to depart from reserves and assimilate into the white community.

The Coranderrk residents vehemently protested this discriminatory law, but despite their efforts, they were unable to prevent its implementation. The 'Half-Caste Act' had devastating repercussions for Coranderrk, resulting in a significant decline in its population and the fracturing of families.

William Barak died at Coranderrk on 15 August 1903 and is buried at the Coranderrk cemetery. He was about 85 years old. Coranderrk eventually closed in 1924 and the last Kulin resident died in 1944.