Significant Dates for Indigenous Australians in June

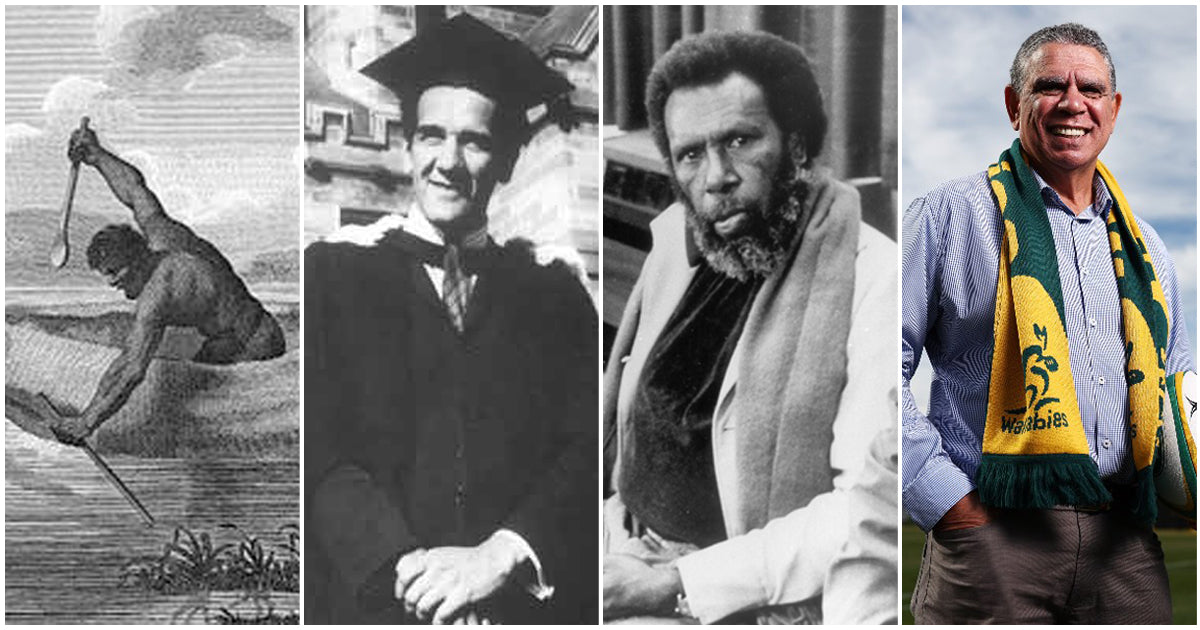

Pemulwuy, Charles Perkins, Eddie Mabo, Mark Ella

In June, we commemorate several significant events for Australia's First Nations people, reflecting our resilience and rich history:

2 June 1902 – Death of Pemulwuy: Pemulwuy, a Bidjigal warrior, led a guerrilla war against British colonisation in New South Wales from 1788 until his death. His fierce resistance and strategic acumen made him a symbol of Aboriginal defiance.

3 June – Mabo Day: Mabo Day marks the 1992 High Court decision recognising Indigenous Australians' land rights, thanks to Eddie Koiki Mabo's relentless campaign. This ruling overturned the doctrine of terra nullius, a pivotal event in the struggle for First Nations justice.

5 June 1831 – Death of Tarenorerer: Tarenorerer, a Tasmanian Aboriginal resistance leader, fought against British colonists using guerrilla tactics. Her leadership and defiance highlight the struggle and resilience of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people.

5 June 1959 – Birth of Mark Ella: Mark Ella, an Indigenous Australian rugby legend, revolutionised the game with his innovative play and leadership. He became the first Indigenous Australian to captain a national sports team.

6 June 1835 – John Batman’s Illusory Treaty: Batman claimed to have secured land from the Wurundjeri people through a treaty, which was later invalidated. The treaty exemplifies the manipulative practices employed during colonial expansion to take control of Indigenous lands.

10 June 1838 – Myall Creek Massacre: The massacre of at least 28 unarmed Indigenous Australians by 12 colonists marked a dark chapter in Australian history. The subsequent trial and execution of some perpetrators were rare acknowledgments of colonial violence, but ultimately ushered in a "conspiracy of silence" to deny officially sanctioned acts of genocide.

16 June 1936 – Birth of Charles Perkins: Charles Perkins, a key figure in Australian civil rights, organised the 1965 Freedom Ride, exposing racial discrimination in regional New South Wales. His activism and public service significantly advanced Indigenous rights and recognition.

20 June 1837 – Death of Tongerlongeter: Tongerlongeter, a Tasmanian Aboriginal leader, led sustained resistance against British colonists. His strategic warfare and personal sacrifices underscore the persistent Aboriginal struggle against colonial oppression.

These events collectively highlight the enduring spirit and struggle of Australia's First Nations people and the ongoing journey towards reconciliation and justice.

2 June 1902 – Death of Pemulwuy

Pemulwuy stands as one of the most iconic Aboriginal resistance fighters in Australian history. A Bidjigal warrior from the Dharug people of New South Wales, Pemulwuy led a determined guerrilla war against British colonisation that began with the arrival of the First Fleet in January 1788.

Pemulwuy was born around 1750 near Botany Bay, an area known as Kamay in the Dharug language. Marked by a distinctive blemish in his left eye, Pemulwuy's uniqueness was recognised early on. Despite the societal norm that might have seen such a child sent back to the land to be reborn, Pemulwuy defied expectations. He excelled in all endeavours, gaining a reputation for his extraordinary skills and spiritual significance. His left foot, damaged deliberately, marked him as a carradhy, or cleverman - a healer and spiritual leader in Aboriginal culture.

Initially, Pemulwuy engaged with the British arrivals, hunting meat and providing it to the struggling colony in exchange for goods. However, by 1790, Pemulwuy's patience with the colonists' encroachments ran out. He launched a fierce and sustained campaign of resistance that would last for twelve years. His leadership and strategic acumen galvanised the Dharug people and other Indigenous groups to join his cause.

Pemulwuy's resistance began in earnest with an attack on a party of colonists near Botany Bay in December 1790. The colonists, including Governor Phillip's gamekeeper John McIntyre, were ambushed, and McIntyre was speared by Pemulwuy. This attack prompted Governor Phillip to launch a retaliatory military expedition, which ultimately failed to capture Pemulwuy.

Over the following years, Pemulwuy led numerous raids on colonial settlements, targeting crops, livestock, and work parties. His tactics caused significant disruption and fear among the colonists. Despite being wounded multiple times, Pemulwuy's resilience and continued defiance only enhanced his legendary status among his people.

In early 1797, Pemulwuy led a major offensive against the settlers at Parramatta. In what became known as the Battle of Parramatta, Pemulwuy and his warriors confronted a combined force of armed settlers and British soldiers. Despite being shot seven times, Pemulwuy survived, further cementing his reputation as invincible.

Captured and imprisoned, Pemulwuy managed a daring escape, reinforcing his legendary status. His resistance, though less intense due to his injuries, continued sporadically. He even reached a form of reconciliation with Governor John Hunter, indicating a complex relationship with the colonial authorities.

Governor Philip Gidley King issued an order in November 1801 for Pemulwuy's capture, dead or alive, offering a substantial reward. Pemulwuy was ultimately killed on or around 2 June 1802 by Henry Hacking, a first mate in the Royal Navy. His death marked the end of a significant chapter in the Aboriginal resistance against colonial expansion.

Pemulwuy's head was severed and sent to England as a trophy, symbolising the colonial power's brutal victory.

The circumstances relating to Pemulwuy's death and the fate of his remains was described by the Sydney Morning Herald in 2003 as "Australia's oldest murder mystery".

Repatriation of the skull of Pemulwuy has been requested by his Aboriginal relatives in Sydney. In 2010, Prince William announced he would return Pemulwuy's skull to its rightful but to no avail. One trail led to the Natural History Museum in London, but the museum has no record of the skull, and it has not yet been able to be located among the estimated 3,000 other remains of Aboriginal people in the UK.

Despite the circumstances of his death, Pemulwuy's legacy has endured. He is remembered as a symbol of resistance and resilience.

Pemulwuy's story is a testament to the strength and spirit of the Aboriginal people in the face of overwhelming odds. The efforts to repatriate Pemulwuy's remains continue, reflecting ongoing respect and recognition for his role in Australia's history.

Pemulwuy's defiance, bravery and leadership have made him a lasting hero to his people and an indelible figure in the broader narrative of Indigenous resistance in Australia. His life and legacy continue to inspire generations seeking justice and recognition for the Aboriginal struggle against colonisation.

3 June – Mabo Day

Every year on 3 June, Australia commemorates Mabo Day, an important occasion that marks the anniversary of a landmark decision in the fight for Indigenous land rights. This day, celebrated during National Reconciliation Week, honours Eddie Koiki Mabo and the historic Mabo v Queensland (No 2) decision by the High Court of Australia. This pivotal ruling, delivered on 3 June 1992, recognised the pre-colonial land interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, fundamentally overturning the doctrine of terra nullius that had dominated Australian law since Captain James Cook's voyage in 1770.

Eddie Koiki Mabo, a Torres Strait Islander born on 29 June 1936, dedicated his life to advocating for Indigenous land rights. His tireless campaign led to the High Court’s decision, which acknowledged that Indigenous Australians had a traditional connection to the land predating colonial claims. Mabo's efforts were not solitary; he was supported by co-plaintiffs James Rice, Father Dave Passi, Sam Passi, and Celuia Salee, whose collective struggle brought about a significant legal and social transformation in Australia.

On the tenth anniversary of the High Court decision in 2002, Mabo’s widow, Bonita Mabo, called for a national public holiday on 3 June to honour this monumental achievement. This call was echoed by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) in 2003, which launched a petition advocating for the establishment of Mabo Day as a public holiday across Australia.

Eddie Mabo Jr., representing the Mabo family, emphasised the importance of such a holiday:

"We believe that a public holiday would be fitting to honour and recognise the contribution to the High Court decision of not only my father and his co-plaintiffs, but also to acknowledge all Indigenous Australians who have empowered and inspired each other. To date, Australia has no public holiday that specifically acknowledges Indigenous contributions and achievements. Mabo Day represents an opportunity to celebrate the truth and justice that Mabo’s legacy symbolises. It is a day that can unite Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in pride and recognition of the country’s rich and complex history. A public holiday would be a celebration all Australians can share in with pride – a celebration of truth that unites Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians and a celebration of justice that overturned the legal myth of terra nullius."

In 2010, a campaign was launched to make Mabo Day a national holiday, highlighting its significance not just for Indigenous Australians, but for all who value justice and reconciliation. While the campaign continues, Mabo Day is already an official holiday in the Torres Shire, where it serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring struggle for Indigenous rights and the progress that has been made.

Mabo Day commemorates Eddie Koiki Mabo’s indomitable spirit and his profound impact on Australian society. It is a day to reflect on the journey towards reconciliation and to honour the contributions of all Indigenous Australians to the nation’s history and future.

Eddie Mabo passed away on 21 January 1992, aged 55.

5 June 1831 – Death of Tarenorerer, Tasmanian Aboriginal resistance leader

Tarenorerer was a renowned Aboriginal resistance leader born around 1800 near Emu Bay, Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania). She was a member of the Tommeginne people, an Indigenous group from northern Tasmania.

Tarenorerer’s early life took a drastic turn when, in her teens, she was abducted and sold to white sealers on the Bass Strait Islands. During her time in captivity, she learned to speak English fluently and took a keen interest in the use and operation of firearms.

In 1828, Tarenorerer returned to her homeland in northern Tasmania. There she gathered a group of men and women to resist the encroaching British colonisers. Demonstrating exceptional leadership and strategic acumen, she trained her warriors in the effective use of firearms. She instructed them to attack the colonisers, or “luta tawin”, at their most vulnerable moments - specifically, after they had discharged their guns and before they could reload. Additionally, she directed her followers to kill the colonist's livestock, such as sheep and bullocks, to disrupt their food supply and economic stability.

Tarenorerer’s resistance efforts quickly caught the attention of George Augustus Robinson, the controller of brutal Aboriginal internment camps on Flinders Island and chief supplier of Aboriginal remains to English “collectors”.

Colonists had informed Robinson that Tarenorerer, whom they referred to as an "Amazon," would stand on hills to orchestrate attacks, hurl abuses at her enemies, and challenge them to face her in combat. Robinson pursued her relentlessly, but she skilfully evaded capture. In September 1830, Robinson’s party narrowly avoided an ambush by her warriors.

Tarenorerer’s resistance continued as she fled to Port Sorell with her brothers, Linnetower and Line-ne-like-kayver, and two sisters. However, she was soon captured by sealers and taken to the Hunter Islands. There, she was "given" to John Williams, known as “Norfolk Island Jack”, and taken by him to Forsyth Island in the Furneaux group to live with other sealers and Aboriginal women.

In December 1830, Tarenorerer devised a plan to kill one of the sealers but was thwarted by Robinson's agents. She was subsequently taken to Swan Island, where her identity was eventually. Fearing that she would incite further revolts, Robinson isolated her. In February 1831, he noted in his diary that nearly all the troubles in the Tasmanian Aboriginal internment camps were traced back to Tarenorerer and her warriors.

Tarenorerer was subsequently moved to Gun Carriage (Vansittart) Island. There, she fell ill and, on 5 June 1831, succumbed to influenza. Her death marked the end of a brave and tenacious fight on behalf of her people in a war for which there are no memorials.

Tarenorerer’s life and legacy stand as a testament to her courage and determination to defend her land and people. Despite the lack of formal recognition or memorials, her story serves as a reminder of the resilience and strength of the Tasmanian Aboriginal resistance against colonial oppression.

5 June 1959 – Birth of Mark Ella, Australian Rugby player

Mark Gordon Ella, AM, is a celebrated Indigenous Australian rugby union footballer, renowned for his exceptional skills and groundbreaking achievements in the sport. Hailing from La Perouse in Sydney, Ella and his brothers Glen (his twin) and Gary were educated at Matraville High School, where they learned to play rugby. All three went on to play for the Australia national team.

Ella played primarily as a flyhalf (five-eighth) and was capped 25 times by the Wallabies, captaining Australia on 10 occasions. His influence on the game, particularly his innovative approach to the flyhalf position, has left an indelible mark on rugby union.

Ella made his debut tour with the Wallabies during the 1979 Australia rugby union tour of Argentina. He then made his Test debut for Australia in the 1980 Bledisloe Cup Test series, where the Wallabies defeated the All Blacks two games to one. This victory was significant as it was the first three-Test series win against New Zealand since 1949 and the first series win over the All Blacks on Australian soil since 1934.

In 1982, Ella was named captain of the Australian national team, becoming the first Indigenous Australian to captain a national sports team. Despite a challenging tour of New Zealand in 1982, where Australia lost one game to two, Ella's leadership and skill were evident. The Wallabies scored an impressive 316 points in 14 matches, including 47 tries.

Ella's most famous achievements came during the 1984 Australia rugby union tour of Britain and Ireland, where the Wallabies achieved rugby union's Grand Slam by defeating the Home Nations in four consecutive Tests. Ella's remarkable performances included scoring a try in each Test, showcasing his extraordinary talent and vision.

Ella's playing style at flyhalf was unique, characterised by his close positioning to the scrum-half, quick decision-making, and exceptional ball-handling skills. His approach involved standing about five meters from the halfback and four meters behind, drawing defenders towards him and creating space for his teammates. This strategic positioning and his adept passing made him a formidable playmaker.

Bob Dwyer, former coach of the Wallabies, lauded Ella as one of the five most accomplished Australian players he had ever seen, emphasising Ella's mastery of the game's structure. Gareth Edwards, in his book "100 Great Rugby Players," highlighted Ella's ability to draw defenders and release the ball quickly, making him a pivotal link in the backline.

After retiring from rugby at the young age of 25 to the shock of the professional sporting world, Ella transitioned into various roles, including working as a director of the Sports and Entertainment Group, serving as sports and events manager for the Port Macquarie-Hastings Council, and coaching with the Wallabies. He also played a significant role at NITV, Australia's free-to-air Indigenous television station, where he became Executive Producer and Head of NITV Sport.

In 2007, Ella published his autobiography, co-written with journalist Bret Harris. His contributions to rugby have been widely recognised, with his induction into multiple halls of fame, including the Australian Rugby Union Hall of Fame, the International Rugby Hall of Fame, and the IRB Hall of Fame.

Mark Ella's impact on rugby extends beyond his playing days. He is frequently cited as one of the greatest players in the history of the sport. David Campese, a former Australian winger, called Ella "the best rugby player I have ever known or seen." Similarly, former Welsh eight-man Eddie Butler ranked Ella as the greatest fly-half of all time, highlighting his influence on the game.

Ella's legacy is further cemented by numerous accolades, including being made a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) in 1984, receiving a Centenary Medal and an Australian Sports Medal in 2001, and being named one of Australian rugby's "Invincibles" by Inside Rugby magazine in 2013.

Mark Ella's contributions to rugby union, both on and off the field, have made him a legendary figure in Australian sports. His innovative playing style, leadership and dedication to the sport have inspired countless players and fans worldwide. Ella's story is a testament to the profound impact one individual can have on the game in the international arena, shaping its future and leaving a lasting legacy.

6 June 1835 – John Batman’s Illusory Treaty with the Wurundjeri people in the Kulin Nation

On 6 June 1835, a significant yet deeply controversial event occurred in Australian history. John Batman, a convict’s son from Van Diemen’s Land (modern-day Tasmania), claimed to have negotiated a treaty with Wurundjeri Elders to secure land around Port Phillip Bay, paving the way for the establishment of Melbourne.

The Wurundjeri people of the Woiwurrung language group in the Kulin nation are the traditional owners of the Yarra River Valley, covering much of the present location of Melbourne.

Batman’s Treaty is often portrayed as a pioneering effort in establishing peaceful relations with Indigenous Australians. However, a closer examination reveals Batman not as a hero but as a manipulative and violent coloniser.

In his journal, Batman described his intentions to establish a “friendly intercourse” with the native people to acquire their land. On 29 May 1835, Batman and his party set out to explore and assess the fertile lands around Port Phillip Bay. His writings depict a land teeming with Indigenous activity - huts, dams, and sophisticated land management techniques like fire-stick farming.

Despite these observations, Batman viewed the land through the lens of colonial exploitation, describing it as “so delightful to the eyes of the sheep farmer.” His narrative glosses over the cultural and spiritual significance of the land to its original inhabitants, reducing their sophisticated agricultural practices to signs of “unused” territory ripe for colonisation.

Batman’s encounters with the local Aboriginal people were sometimes marked by exchanges of gifts, which he interpreted as transactions. On 6 June 1835, Batman claimed to have met an Aboriginal family and distributed various goods in exchange for their guidance. He was then supposedly led to the tribal “chiefs” whose marks appeared on a treaty that Batman later used to assert his purchase of approximately 600,000 acres of land.

The treaty, however, was based on a profound cultural misunderstanding and deception. Batman’s journal admits that he made the chiefs’ signatures himself, casting doubt on the legitimacy of his claims. The exchange of gifts was likely perceived by the Wurundjeri as acts of hospitality rather than a land sale. The idea of selling land was alien to the Aboriginal worldview, where land is a communal and spiritual resource, not a commodity.

Batman quickly returned to Launceston, where he, along with surveyor John Helder Wedge, mapped the claimed land, naming geographical features after members of the Port Phillip Association. This act of naming further solidified their colonial intentions and disregard for the existing Aboriginal names and significance.

In August 1836, Governor Richard Bourke of New South Wales declared Batman’s Treaty invalid, as the land was deemed under the jurisdiction of the Crown, making any private claim null. Despite this, the Port Phillip Association received compensation for their efforts, while the traditional owners received nothing for the loss of their lands and violent disruption of their lives.

John Batman’s actions were not those of a benevolent negotiator but of a self-serving coloniser. He played a significant role in the violent dispossession and suffering of Aboriginal people, both in Tasmania and mainland Australia. His involvement in the Black War in Tasmania, where he participated in massacres of Aboriginal people, further tarnishes his legacy.

Batman’s Treaty is often cited as a unique attempt to engage with Indigenous people through negotiation rather than outright conquest. However, the truth reveals a tale of deception, cultural insensitivity and exploitation. Batman’s so-called treaty was a sham, an attempt to legitimise the theft of land through duplicitous means.

In any examination of events in Australian history like Batman’s Treaty, it is crucial to reassess the narrative that frames colonial figures like John Batman as heroes. The true story of Batman is one of violence, exploitation and deceit. Recognising this dark chapter in history is essential in understanding the broader context of colonialism in Australia and the enduring impact on Aboriginal communities.

By acknowledging these historical truths, Australians can move towards a more honest and inclusive narrative that respects the experiences and rights of its First Nations people.

Batman’s Treaty should serve as a reminder of the injustices of the past and a call to address the lasting consequences of colonialism in the present.

10 June 1838 - Myall Creek Massacre

The Myall Creek massacre saw at least 28 unarmed Indigenous Australians brutally killed by twelve colonists, near the Myall Creek by the Gwydir River in northern New South Wales.

Eleven convict stockmen led by “free settler” John Henry Fleming, murdered a group of Wirraayaraay people, part of the Kamilaroi nation, including women, children and elderly men, who had sought refuge at Myall Creek station.

The stockmen tied the victims with a long rope, led them away and slaughtered them primarily with swords. Only one woman was spared temporarily. They then burned the bodies over two days.

The first trial began on 15 November 1838, with 11 defendants. John Henry Fleming escaped prosecution. Key witness George Anderson testified about the massacre. Despite strong evidence, the jury found all not guilty.

Attorney General John Plunkett then initiated a second trial against seven of the original defendants. This trial saw more detailed testimony from Anderson. On November 30, the jury found the seven men guilty of the murder of a six-year-old Aboriginal child. They were sentenced to death by hanging and executed on 18 December 1838.

Four men from the first trial were not retried due to the absence of a key witness, an Aboriginal boy who had disappeared in mysterious circumstances.

The verdict sparked significant controversy. Many colonists, including some newspapers like the Sydney Morning Herald, vocally opposed the executions, viewing the massacre as a necessary act of colonial expansion.

Criticisms were racially charged, arguing against the execution of white men for killing Aboriginal people. The Sydney Herald's editorials openly called for genocide against Indigenous Australians.

The second trial was regarded as the first and only successful prosecutions of colonists for massacring Aboriginal people in Australia, marking a significant legal precedent. However, the outcry from colonists led to fewer prosecutions for similar acts in the future, as silence and collusion became more common.

Despite the Myall Creek trials, many subsequent massacres, like the Waterloo Creek massacre, where it was estimated that over 100 Aboriginal people were murdered went unpunished, reflecting colonial acceptance of officially sanctioned violence against the original owners of the lands they had seized.

In his book, Blood on the Wattle, Bruce Elder says that the successful prosecutions resulted in pacts of silence becoming a common practice to avoid sufficient evidence becoming available for future prosecutions.

Another effect, as two Sydney newspapers reported, was that poisoning Aboriginal people became more common as being "much safer". Many massacres went unpunished due to these practices, as what has been called a “conspiracy of silence” fell over the killings of Aboriginal people.

The Myall Creek massacre and the subsequent trial and hanging of some of the offenders had a profound effect on the colonial landholders and their dealing with Indigenous people throughout all sections of the colonial Australian frontiers.

In Queensland, the most populated section of the continent in terms of Indigenous people, there was almost unanimous agreement in the first parliament that no white man should ever be prosecuted for the killing of a black.

On 10 June 2000, a memorial was unveiled near Myall Creek to honour the victims. The memorial has been vandalised multiple times, reflecting ongoing racial tensions.

The site was listed on the Australian National Heritage List in 2008 and the New South Wales State Heritage Register in 2010. A ceremony is held each year on 10 June to commemorate the victims, supported by the Friends of Myall Creek organisation.

On 9 June 2023, ahead of the 185th anniversary of the massacre, the Sydney Morning Herald issued an editorial apology for its role in spreading racist views and misinformation during the time of the trials. The trials exposed deep-seated racial prejudices and a pervasive colonial mindset that viewed the extermination of Indigenous people as a necessary part of nation building.

The Myall Creek Massacre stands as a profound reminder of the violence and injustice that accompanied Australia's colonial history. It serves as a call to acknowledge this past and ensure that it is not forgotten.

16 June 1936 – Birth of Charles Perkins, Aboriginal activist

Charles Nelson Perkins AO, usually known as Charlie Perkins was born on 16 June 1936 in the old Alice Springs Telegraph Station to Hetty Perkins, originally from nearby Arltunga, and Martin Connelly, originally from Mount Isa, Queensland. His mother was born to a white father and an Arrernte mother, while his father had an Irish father and a Kalkadoon mother.

Perkins married Eileen Munchenberg, a descendant of a German Lutheran family, on 23 September 1961 and had two daughters (Hetti and Rachel), and a son (Adam). His granddaughter through Hetti is actress Madeleine Madden.

Perkins is best known for his civil rights activism. His organisation of the Freedom Ride in 1965 was a pivotal event in Australian civil rights history. By exposing and protesting the discrimination faced by Aboriginal people in rural towns, the Freedom Ride played a crucial role in raising national awareness and sparking public debate about racial inequalities in Australia.

Perkins was also a strong advocate for the "yes" vote in the 1967 referendum to allow for the inclusion of Aboriginal people in censuses and giving the Parliament of Australia the right to introduce legislation specifically for Aboriginal people. This event a significant step towards legal and social recognition of Indigenous Australians.

Perkins’ career in the public service, including his role as Secretary of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, highlighted his commitment to improving the lives of Indigenous Australians through governmental channels. His outspoken nature and passion often put him at odds with political leaders, but his influence was undeniable.

Perkins’ founding of Aboriginal Hostels Limited provided crucial support and temporary accommodation for Indigenous people, demonstrating his practical approach to addressing immediate needs within the community.

Perkins' achievement as the first Indigenous Australian man to graduate from university in 1966 served as an inspirational milestone, breaking educational barriers and paving the way for future generations of Indigenous scholars.

Perkins’ legacy is honoured through various memorials and awards, including the Dr. Charles Perkins AO Memorial Oration and Prize at the University of Sydney, the Charlie Perkins Trust scholarships for study at Oxford, and the Charles Perkins Centre at the University of Sydney.

Beyond his activism, Perkins made significant contributions to Australian soccer as a player, coach and administrator. His leadership roles in the sport, including as vice-president of the Australian Soccer Federation and chairman of the Australian Indoor Soccer Federation, highlighted his versatility and influence across different fields.

Perkins' autobiography, "A Bastard Like Me," published in 1975 offers a personal and insightful account of his life, struggles, and achievements, providing an important resource for understanding the challenges and triumphs of Indigenous Australians.

Perkins was named one of Australia's Living National Treasures and honoured with multiple awards, Perkins' life and work continue to be celebrated and remembered for their lasting impact on the nation.

Perkins' life story and accomplishments continue to inspire new generations of Indigenous Australians and activists committed to social justice and equality.

The continuing commemorations and initiatives in his name underscore the enduring relevance of his work and the ongoing need to address the historical and contemporary issues facing Indigenous Australians.

Perkins died in Sydney on 19 October 2000 of renal failure. His legacy is one of resilience, courage and transformative action. His efforts not only brought attention to the injustices faced by Indigenous Australians but also laid the groundwork for ongoing advocacy and change. His life and work remain a testament to the power of activism and the enduring struggle for equality and justice.

20 June 1837 – Death of Tongerlongeter, Tasmanian Aboriginal resistance leader

Tongerlongeter, a renowned warrior and leader of the Poredareme clan of the Oyster Bay nation in Tasmania, holds a significant legacy as a fierce defender of his people and their lands. His life and actions are emblematic of the broader struggle of Indigenous Australians against colonial invasion, displacement and genocide.

Tongerlongeter played a central role in the Black War (1823-1831), leading guerrilla warfare tactics against British colonists. His leadership in mounting over 493 attacks demonstrates his strategic acumen and unwavering commitment to resisting colonial encroachment.

Despite the declaration of martial law and the extensive military campaign known as the Black Line, Tongerlongeter’s leadership ensured that his people continued to resist fiercely, embodying resilience and defiance in the face of overwhelming odds.

Tongerlongeter’s personal loss, including the abduction of his first wife and the death of his son, Parperermanener, highlights the profound personal sacrifices made during this period.

Even in exile on Flinders Island, Tongerlongeter emerged as a principal leader, advocating for his people’s wellbeing and representing them in dealings with colonial authorities.

Despite his significant contributions, Tongerlongeter’s grave remains unmarked, and there is no formal memorial recognising his efforts and sacrifices. This lack of recognition points to the broader historical amnesia surrounding Indigenous resistance leaders.

In recent years, there has been a growing appreciation for Tongerlongeter’s role in Tasmanian and Australian history. His story is increasingly acknowledged and admired by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of Australia’s colonial past.

Tongerlongeter’s persistent advocacy for his people’s rights and return to their Country reflect his enduring commitment to their survival and dignity.

While Tongerlongeter has no known direct descendants, his legacy as a resistance leader continues to inspire contemporary Indigenous activism and efforts towards reconciliation and recognition of historical injustices.

Tongerlongeter’s legacy is a powerful testament to the strength and resilience of Indigenous Australians in the face of colonial oppression.

His leadership during the Black War and his continued advocacy for his people in exile highlight the enduring spirit of resistance and the importance of honouring and remembering those who fought to protect their land and culture.

As historical amnesia fades, Tongerlongeter’s story serves as a crucial narrative in the broader context of Australia’s history and a reminder of the ongoing journey towards truth and reconciliation.

The timeline of events commemorated in June serves as a poignant reminder of the rich history and enduring resilience of Australia's First Nations people.

From the courageous resistance of warriors like Pemulwuy and Tarenorerer to the landmark Mabo decision recognizing Indigenous land rights, each event encapsulates a significant chapter in the ongoing struggle against colonisation and injustice.

Recognition of outstanding individuals such as Mark Ella and Charles Perkins celebrates the achievements and contributions of Indigenous Australians in sports and civil rights, respectively.

Meanwhile, the Myall Creek Massacre and John Batman's illusory treaty shed light on the darker aspects of colonial history and the manipulative tactics used against Indigenous communities.

Finally, the defiant leadership of Tongerlongeter exemplifies the unyielding spirit of resistance among Tasmania’s Aboriginal people.

Together, these events underscore the profound impact of Indigenous resistance and activism on shaping Australia's national consciousness. They highlight the necessity of acknowledging past injustices and the importance of continuous efforts toward reconciliation and justice.

By commemorating these significant moments, we honour the legacy of Australia's First Nations people and reaffirm our commitment to a more inclusive and equitable future.